Life is good for Chris Cline. Forbes ranks him as the 339th wealthiest person in America, with a net worth of $1.9 billion. He owns a 150-acre estate in Beckley, West Virginia and a 34,000 square foot ocean front mansion in Palm Beach, Florida. He also owns the 164-foot luxury yacht he’s dubbed Mine Games, which has five staterooms and a two-person submarine. He dated his neighbor Elin Nordegren, the ex-wife of Tiger Woods, for a year until she called it off mid-2014.

As the name of his yacht suggests, Cline made his money in mining, mostly coal mines, but he also owns Gogebic Taconite, or GTac, a Florida-based company seeking permits to construct an open pit iron mine in the scenically spectacular Penokee Hills of Iron and Ashland Counties in Wisconsin’s North Woods. The recent disclosure that GTac contributed $700,000 to the Wisconsin Club for Growth, which in turn ran ads supporting Gov. Scott Walker, has raised questions about how much political influence was exerted behind closed doors to pass legislation clearing the way for this iron mine. The ferrous mining bill (Act 1), passed in March 2013, and largely written by GTac, seriously weakened Wisconsin’s environmental regulations and eliminated the contested case hearing where citizens could challenge the mine permit.

This was the way Cline learned to do business in the coalfields of Appalachia and Illinois: keep a low public profile while exercising power over government. Can a company like GTac, with no iron mining experience, construct one of the world’s largest open pit mines at the headwaters of the Bad River watershed without harming its plentiful waters flowing into Lake Superior? If Cline’s long track record in coal mining, and Gtac’s past history is any indication, Wisconsin residents have cause for concern.

How Cline Became King Coal

Chris Cline comes from a coal mining family in Beckley, West Virginia. His grandfather mined coal with a pickax a century ago. His father would pay young Chris a penny a bag to excavate dirt from under the front porch. His corporate bio says that in 1980, Chris, at age 22, followed in the footsteps of his grandfather and father and began working as an underground coal miner in southern West Virginia and “quickly moved into management.” His father, meanwhile, had bought out a mining partner’s shares in a coal mine to give Cline when he was 21 years old. By 1990, Chris Cline had formed his energy and development group, the Cline Resource and Development Group.

Cline went on to develop extensive coal mining, processing and transportation facilities in Appalachia and the Illinois Basin. According to Bloomberg Markets Magazine, Cline “became a billionaire by betting on a dirty fuel the world can’t get enough of.”

His corporate bio says Cline “learned to use unique tools to motivate his workforce to develop and run low-cost mining operations,” without specifying what those tools were. In 1999 he closed down a West Virginia mine when workers voted to join a union. He then reopened the mine without union workers. (Cline declined to do an interview or answer questions for this story.)

In 2003 Cline shifted its investment from declining Appalachian coal reserves to much cheaper Illinois Basin coal. That was the year new federal regulations went into effect requiring power plants to install scrubbers to reduce sulfur dioxide emissions. This created a demand for high-sulfur Appalachian coal that could now be used by plants with the new scrubbing technology. This made Cline a billionaire and allowed him to expand his coal business. By 2009 Cline had acquired more than 3 billion tons of coal in southern and central Illinois. Bloomberg Markets Magazine dubbed Chris Cline as the “New King Coal.”

However, the extraction of coal from underground longwall mining causes subsidence that damages farmland and disrupts surface and groundwater resources. For example, at Cline’s Shay 1 mine in Macoupin County, IL, the subsidence has completely altered drainage patterns of subsided lands. Citizens Against Longwall Mining (CALM) has described this as “a bathtub effect where lands that previously drained will fill up with standing water.”

The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel has reported that the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency accused one of Cline’s companies of delaying the cleanup of groundwater contamination at its Shay 1 mine in Macoupin, Ill. It is one of four mines in Illinois owned by Chris Cline and his Foresight Energy company (which he formed in 2006). Altogether, these mines have violated effluent standards in their wastewater permit 53 times over the past three years, according to EPA records.But Cline’s environmental track record is far worse than 53 permit violations. According to Devon Cupery, one of the producers of the documentary film, “Wisconsin’s Mining Standoff,” Cline’s coal mines in West Virginia and Illinois have been cited for over 8,000 federal safety violations since 2004. More than 2,300 were “significant and substantial” violations with the potential for injury, illness or death.

Cline, however, told Bloomberg Markets Magazine that government efforts to reduce U.S. greenhouse gas emissions from burning coal are misplaced. When he learned that his children’s teachers in Palm Beach, Florida had shown Al Gore’s film, An Inconvenient Truth, he asked them to distribute literature that showed climate change may be caused by clusters of sunspots or the Earth wobbling on its axis, not just carbon. When they refused, citing the lack of scientific support for such theories, he complained to school fundraisers. “As far as the social acceptability of coal, I like to think I’m part of supplying the cheapest energy in America.”

Cline told a Bloomberg reporter that Massey Energy’s CEO Don Blankenship, who headed the company during the Upper Big Branch Mine disaster that occurred in April 2010 , was one of the coal industry’s “most talented leaders… Don thinks his convictions are morally correct and follows them.” The coal dust explosion at the Upper Big Branch Mine killed 29 miners and was the worst coal mining disaster in 40 years. An independent commission appointed by West Virginia Governor Manchin concluded that Massey “operated its mines in a profoundly reckless manner… and 29 miners paid with their lives.”

The report also concluded that Massey used its power “to attempt to control West Virginia’s political system” and its oversight agencies. Politicians were afraid to oppose the company because it “was willing to spend vast amounts of money to influence elections.”

That same approach has been followed by Cline, with tremendous success.

Regulatory Capture

As early as the 1950s and 1960s, political scientists used the term “regulatory capture” to describe the situation where a regulatory agency abandons its responsibility to serve the public interest and becomes the servant of corporate interests that dominate the industry it is supposed to regulate. Scholars of both the left (Gabriel Kolko) and the right (George Stigler) challenged the prevailing assumption of a neutral regulator or public servant. Their studies showed a widespread pattern where “regulations are routinely and predictably ‘captured’ and manipulated to serve the interests of those who are supposed to be subject to them, or the bureaucrats and legislators who write or control them,” as Amitai Etzioni has written.

West Virginia has long been a state where coal mining companies used legal strategies and donations to politicians to help them evade or stall or weaken regulations. Meanwhile, charitable donations like the Cline Family Foundation’s $5 million gift to West Virginia University’s School of Medicine and Department of Intercollegiate Athletics helps to soften any opposition to the adverse effects of mining.

Cline exported this style of politics to Illinois after he moved into mining there.The Illinois Times has reported that mining companies owned by Cline have contributed thousands of dollars to a Democratic political committee controlled by one of the state’s top mining regulators. These contributions were made while Cline’s companies were seeking coal mining permits from the Illinois Department of Natural Resources.Between 2006 and the present, three of Cline’s companies – Foresight Energy, Macoupin Energy and Hillsboro Energy – have contributed a combined total of more than $1.5 million to Illinois politicians including Governor Pat Quinn, House Speaker Michael Madigan and Illinois Supreme Court justice Mary Jane Theis. Will Reynolds, a former chair of the Illinois Sierra Club told the media “there should be a federal investigation into whether the Cline companies got special treatment in permitting and safety because of campaign contributions. It looks like money was used to buy favors.”

Cline had expanded his reach by creating Foresight Energy in 2006, which in turn, is a wholly owned subsidiary of Foresight Reserves, a privately held company. In 2007, Riverstone Holdings, a private equity firm specializing in energy and power projects, became a minority owner of Foresight Reserves. Riverstone, in turn, is part of the Carlyle Group, the third largest private equity firm in the world. The Economist magazine describes the Carlyle Group as “deeply embedded in the iron triangle where industry, government and the military converge” in a way that recalls President Eisenhower’s warning about the threat to democracy from the “military-industrial complex”

Problems in Illinois

In the case of the Shay Mine owned by Foresight Energy, the Illinois EPA says the company has been too slow in cleaning up the sulfate, iron, manganese and total dissolved solids that have leached into the groundwater under the property. The pollution comes from coal slurry produced during coal processing and can contain arsenic, heavy metals and other pollutants. Millions of gallons of slurry are stored on site in massive unlined slurry impoundments with walls more than 100 feet high.

The situation now requires urgent action because pollutants in the groundwater are spreading and have been found outside of the mine’s property. According to the Illinois Sierra Club, “this facility has contributed to groundwater and surface water contamination for several years with no penalties.” In 2013 the Illinois EPA referred the case to the state attorney general’s office for enforcement; EPA spokesperson Andrew Mason said the agency “feels that the seriousness and scope of the violations makes legal action the most appropriate path forward.”

Other problems arose with the Deer Run Mine in Hillsboro, one of the largest longwall coal mines in Illinois. The coal reserves at the mine are leased to Hillsboro Energy, LLC, owned by the Cline Group. The CEO of Hillsboro Energy is Dwayne Fransico, formerly the president of Massey Energy’s Aracoma Coal Company. He was the president of Aracoma when the company pleaded guilty to “willful” safety violations in the 2006 mine fire that led to the suffocation deaths of two workers there.

When the Illinois Department of Natural Resources’ Office of Mines and Minerals approved the Deer Run mine permit in 2009 there was no mention of a massive coal slurry impoundment to be located within the city of Hillsboro. After the permit was approved, local residents learned the mine was allowed to construct an 88-foot tall impoundment that will cover one square mile and is next to a hospital, school, nursing home and day care center. It is rated as a high hazard dam because if the impoundment were to fail, it would result in loss of life and property in Hillsboro and Schram City and could send pollution downstream into Old Lake Hillsboro.

The Illinois Sierra Club and others asked for an administrative review hearing to object to the Illinois Department of Natural Resources coal slurry impoundment permit because the permit was incomplete and misleading. This was just the beginning of the controversy.

In 2011 local residents were informed a second high-hazard coal slurry impoundment would be constructed next to the first because the first impoundment was designed to last just five years. The impoundment would be twice the size of the first and be located in the City of Hillsboro. According to Citizens Against Longwall Mining, the Deer Run mine secured a revised permit from the Illinois DNR allowing it “to build the entire base of the high hazard coal slurry impoundment and begin dumping coal slurry there before any opportunity for public comment, and before the mine received a dam permit from IDNR…”

In response to citizen complaints, the Illinois Attorney General’s Office sent a letter to IDNR in 2011 raising concerns about whether there was adequate public notice and opportunity for public participation in the permit decision. Rather than halt construction of the impoundment until these issues were resolved, the IDNR granted the mine an emergency dam permit allowing the mine to proceed with construction before responding to citizen complaints. In 2013 a new IDNR hearing officer dismissed CALM’s petition to challenge the impoundment dam permit.

Cline Comes to Wisconsin

In July 2011, Gogebic President Bill Williams spoke to a crowd at the Deep Water Grill in Ashland, Wisconsin. He cited his previous experience at the Cobre Las Cruces (CLC) open pit copper mine near Seville, one of the largest in Spain, as an example of environmentally safe mining. This same technology, he claimed, would eliminate toxic runoff from the massive waste piles at its proposed Penokee Hills iron mine.

In fact, there have been big problems at the CLC mine. In January 2014 the Seville Office of the Environment in Spain filed criminal charges against Williams and two others for arsenic contamination of an aquifer while he was director of mining for CLC from January 2006 to January 2011. Cobre Las Cruces is owned by the Canadian company First Quantum Minerals, which had purchased the mine from Inmet Mining Corp. in a hostile takeover in 2013.

Mining companies routinely “dewater” mine sites by pumping out underground water at staggering rates to keep the mine accessible as it drops below the water table. When the CLC mine opened in 2009 the company began pumping groundwater out of the open pit as part of the dewatering process. When the company re-injected the wastewater back into the aquifer on the same property it was a violation of the mine’s permit and resulted in concentrations of arsenic in local groundwater well above the maximum permitted for human consumption, prosecutors contend. The aquifer was reserved for irrigation and human consumption in times of drought.

First Quantum Minerals maintains the company and its directors will be cleared of the charges, and Williams told the Journal Sentinel the mine built a treatment system to clean the water before injecting it back into the groundwater. However, according to a story by the Wisconsin Citizens Media Cooperative, Spanish authorities charged the mining company promised an innovative, new treatment system and later followed a different approach, illegally extracting clean water and re-injecting wastewater back into the aquifer. Whether Williams will be extradited to stand trial in Spain remains to be seen. Bob Seitz, a spokesperson for GTac, told the JS the case would have no impact on GTac’s operation in Wisconsin.

Williams gave a deposition on September 7, 2010 to answer questions about his role in CLC’s numerous permit violations. Four months later, he left this job to become president of Gogebic, which is based in Florida but has an office in Hurley Wisconsin. Gtac’s interest in the mine began in 2010, before Williams joined the company and around the time that Cline Resource and Development Group purchased Gtac.

In Wisconsin, Cline, Williams and their supporters followed the West Virginia style of buying political influence. Pro-mining groups gave Gov. Walker and state legislators almost $16 million, according to the Wisconsin Democracy Campaign. Documents recently released in the John Doe investigation of Walker’s campaign show that GTac contributed an additional $700,000 to the Wisconsin Club for Growth, an organization directed by the governor’s campaign adviser, which has run ads supporting Walker. Walker claims he was unaware of this donation to his campaign. Nonetheless, the governor met with Gogebic lobbyists to draft an iron mining bill shortly after taking office in January 2011, the same month that Williams took over as GTac president. GTac lobbyists were heavily involved in crafting the language of a new mining bill which eliminated restrictions on dumping mine waste in wetlands. The new language stipulated that iron mining will result in adverse impacts to wetlands and that such impacts are presumed to be necessary.

The bill was defeated by one vote (17-16) in the Wisconsin Senate in March 2012. To insure a Republican majority the next time the bill came up for a vote, Wisconsin Manufacturers and Commerce and others spent almost $2 million to defeat Senator Jessica King (D-Oshkosh) because she had voted against the ferrous mining bill. The WMC spent $964,603 and #Wisconsin Club for Growth# spent $919,400 in attack ads in the last three weeks before the November 2012 election, as the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reported. She was defeated by Republican Rick Gudex by 600 votes.

The Republican-controlled Assembly ultimately passed the bill. “Because Wisconsin Club for Growth’s fundraising and expenditures were being coordinated with Scott Walker’s agents at the time of Gogebic’s donation, there is certainly an appearance of corruption in light of the resulting legislation from which it benefited,” argued Dean Nickel in a legal filing. Nickel is the former head of the state Department of Justice’s Public Integrity Unit who investigated the fund-raising scheme for the state Government Accountability Board.

Everything, in short, went swimmingly for Cline and company. But he was to learn that Wisconsin is not West Virginia, largely due to a long history of grass roots opposition to mining led by Indian tribes located in the state.

Unexpected Opposition

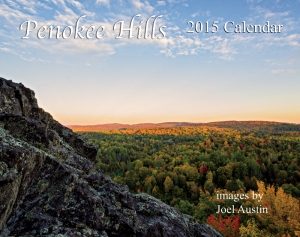

The water-rich Penokee Hills of northern Wisconsin are two parallel ridges that rise 1,200 feet above nearby Lake Superior in a stunningly scenic region. Over 200 inches of snow falls on the Penokees each year, providing plentiful clean water for the Penokee aquifer, the waterfalls in Copper Falls State Park and Lake Superior. The surface and groundwater that flows off the Penokee Hills feeds several major rivers (the Bad, Marengo, Montreal, and Brunsweiler) and provides drinking water for the city of Ashland and nearby towns. The water also feeds the Kakagon/ Bad River Sloughs where the Bad River Ojibwe Tribe maintains the largest natural wild rice bed in the Great Lakes basin. Forty percent of all the wetlands on the Great Lakes are on the Bad River Reservation. This wetland complex has been called “Wisconsin’s Everglades.”

Now imagine a mountaintop removal operation, which blasts the top off the Penokee Hills to extract a low-grade iron ore deposit hundreds of feet below. This would create the largest open pit iron mine in the world, some 4 miles long by 1.5 miles wide and 1,000 feet deep. Over a billion tons of waste rock and tailings created during the projected 35-year life of the mine would be dumped at the headwaters of the Bad River watershed where it could leach toxic metals into the largest undeveloped wetland complex in the upper Great Lakes. Seventy-one miles of rivers and intermittent streams flow through the proposed mining area, emptying into the Bad River and then into Lake Superior.

For the Bad River Ojibwe Tribe, the proposed mine is a literally a life or death issue that could have a disastrous impact on their way of life. When tribal leaders met with Governor Walker in September 2011, they asked that any new mine legislation be based on sound scientific principles. None of the tribe’s 10 principles were considered in drafting the iron mining bill.

The Ojibwe are leading the opposition to the mine, following in the footsteps of other tribes who have opposed mining in Wisconsin. In 1990 the Lac du Flambeau Chippewa tribe joined with environmental and sport fishing groups to oppose Noranda Minerals’ plan to open the Lynne mine in Oneida County, 30 miles south of the Lac du Flambeau reservation. At stake was the contamination of the rich fishing and hunting grounds around the Willow Flowage. The unexpectedly strong opposition, combined with questions about the mine’s potential damage to wetlands, convinced Noranda to withdraw in 1993.

In 1995 the Mole Lake Sokaogon Chippewa became the first Wisconsin tribe granted independent authority by the EPA to regulate water quality on their reservation. The tribe was ready to exercise this authority to protect their wild rice beds from the proposed Crandon mine when the mine owners (BHP Billiton) withdrew from the project and sold the land and mineral rights to the Mole Lake Chippewa and Forest County Potawatomi tribes in 2003. The opposition the company encountered was likely a key reason for the withdrawal.

Now the Bad River Chippewa tribe has asserted their authority under the Clean Water Act to enforce tribal standards on its reservation. Six Wisconsin Chippewa tribes, led by the Bad River, asked the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to conduct an independent review of the environmental effects of GTac’s proposed mine on federally-protected treaty rights and resources before the plan is reviewed by state regulators and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Shortly after the tribes met with the EPA, GTac announced that its plans to submit its application for the Penokee Hills iron mine will be delayed at least a year.

After spending millions to secure legislation it largely wrote to speed up the permit review process, Cline and his company are no closer to a mine permit let alone any kind of social license to operate, which is now seen as essential for any large scale project by mining investors. But Cline has a history of finding ways to get around mining regulations and there is no sign that Walker or the legislature are backing off on the mine. The battle, in short, is far from over.

Al Gedicks is emeritus professor of sociology at UW-La Crosse and the author of Resource Rebels: Native Challenges to Mining and Oil Corporations (South End Press, 2001). His earlier story for us, “The Fight Against Wisconsin’s Iron Mine,” can be found here.

Original Post: http://urbanmilwaukee.com/2014/10/29/how-chris-cline-became-filthy-rich/3/